Journalism has its perks.

So I once found myself a willing onlooker as the cameras of Business Plus TV – Pakistan’s first satellite channel back in 2004, where I had some say in the newsroom – as Punjab chief minister Chaudhary Pervez Elahi welcomed former Indian prime minister IK Gujral.

They talked in Punjabi, Gujral’s delivery crisper and Elahi’s lazier and more laid back as usual, and the guest asked if the central jail in Gujrat, the host’s hometown, was still inside the city.

“We moved it outside some years ago,” Elahi said in Punjabi, the same language the question was asked in.

“You see, I’ve been there,” Gujral snapped back, in English.

“In fact there was a time when both my parents and I were in jail, different ones, but at the same time!”

He extended his hand forward – typical informal Punjabi perversion of the famous American high-five.

This was during the Quit India movement just after the Cripps Mission crashed, and the Subcontinent prepared for what would ultimately be a historic and messy surgical division on religious grounds even though Muslims, Hindus, Christians, Jews, Buddhists and Zoroastrians had lived side by side for more than a thousand years.

Yet here was Gujral, decades after partition – after life as an activist, diplomat, politician and 12th prime minister of India – back in Lahore where he’d first started his politics by joining the All India Students Federation and Communist Party of India while studying at the famous Forman Christian (FC) college. Then, and for half a century before and after, FC College was considered the second-best institution in the city and country – after the famous Government College Lahore.

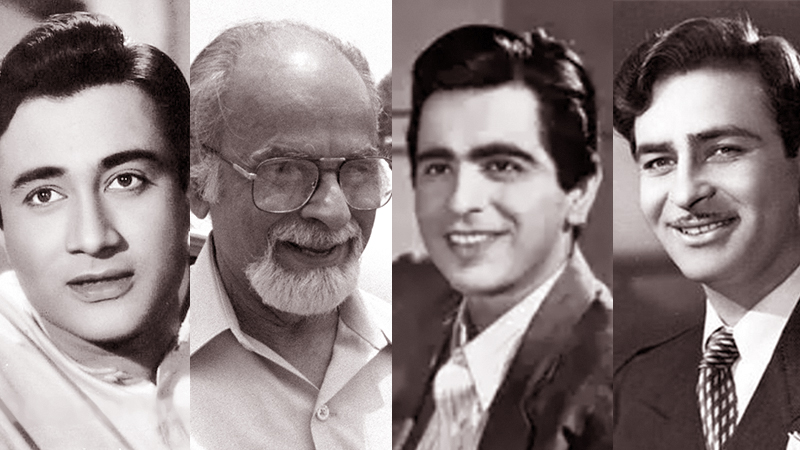

A few years earlier, when I was in my final years at Govt College, I saw famous Indian actor Dev Anand sobbing at the college’s famous amphitheater next to the English department; where he studied literature as he completed his graduation in 1943 (Gujral would be in jail at that time). He was part of Indian PM Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s famous bus trip to Lahore in 1999, and later mentioned with great emotion in his autobiography how the trip to his alma mater brought back memories from once upon a time.

These stories just scratch the surface of the trend that sees people born on either side of the border braving the orgy of blood and murder to make the migration during partition to the other, but never breaking the bond with their real roots. Indeed, the early political, academic and social histories of both Pakistan and India is littered with such examples.

But it surprises me that such people, especially those that grew to prominence, never used the weight of their personalities to push for peace after the divide; to lean on their governments to accept the brotherly bond that still existed between ordinary people despite the bitterness of partition.

Dilip Kumar might never have become the Abhinay Samrat (Emperor of Acting) that Bombay made him if he had stayed as Yousaf Khan in Peshawar, where he was born in 1922. But surely his influence could have pushed many more aspiring artists from the city, which he held close to his heart and would reminisce about till his last days, to pursue their dreams across the border.

Kumar grew up in the same neighbourhood as Raj Kapoor, the fabled Qissa Khwani Bazar. This was the real reason for the close ties between the two families, long before their stars shined so brightly in Bollywood. Kumar’s ancestral home was declared a national heritage in 2014 by the Pakistani government, and the famous Kapoor Haveli is being converted into a museum by IMGC Global Entertainment with the support of the KP (Khyber Pakhtunwa) provincial government.

Sadly, that’s where this story ends. There are many, many more such examples, of course, some of which openly called for better ties, more trade between India and Pakistan. But not to the point of getting their governments to budge.

A rare opportunity presented itself when General Musharraf, born in Delhi in 1943, offered the ultimate compromise – demilitarisation of the most bitterly disputed area and eventual peace, in which the military would be on board. But that, too, fizzled out. His foreign secretary of the time, Shamshad Ahmad Khan – one of Pakistan’s most respected civil servants – lights up every time he recounts how his Indian counterpart arranged a visit to his old family haveli in Indian Punjab, how he could literally see her mother go about her chores like in the old days.

More than seven-and-a-half decades after partition, Pakistan and India have emerged as two of the world’s youngest countries – the majority of their respective populations falling between the ages of 18 and 34. These bright young men and women have little understanding, and no memory, of the disputes that they are supposed to duel over till the end of time. Yet they must live in constant enmity towards each other even though opening the borders for trade and travel would help reduce poverty and advance society on both sides.

My own father was born in Ajmer in 1942. At barely five years of age his world turned when he had to leave the tiny town of Beawar in Rajasthan, where my grandfather taught English and geography, for Karachi with little more than the clothes on his back. His generation has accepted partition, but mine could never understand why Pakistanis and Indians cannot live as happy neighbours, where families like mine can easily visit their ancestral homes. – The writer is a senior journalist and researcher based in Lahore, Pakistan

Leave a Reply