I haven’t really understood why he doesn’t talk much or want to explain how he managed to get on to the Forbes Under 30 list, but the Studio Berçot, Paris-educated Alan Alexander Kaleekal is an enigma of sorts. Maybe he is following in his master Tunisian couturier Azzedine Alaia’s footsteps.

Kaleekal was part of the Ramie Project, (a venture between the French Embassy in India and the Meghalaya Government to develop a new Ramie fabric). He created an installation which was later displayed at the Cité de la Dentelle et de la Mode (Museum of Lace and Fashion), Calais, France from June 17-December 30, 2022.

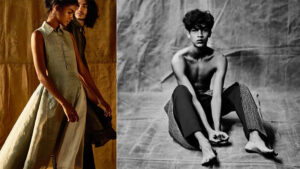

The aim was to market this fibre which grows without any fertilizer or water, and thus has no carbon footprint. His fascination with childhood is constant – he calls it an experiment on abstraction of garments, with deconstruction used to reconstruct.

The fabric is silk-like, but with an attitude of linen, doesn’t crumple and 200 metres of was woven in off-white, natural and black. The beauty is it regulates body heat and requires no chemicals to produce.

But that is not all, the man of few words also worked on the Travancore Revival Project, developing a 150-year-old handwoven fabric from a photograph taken in the 1860s of the Travancore Royal family.

“The process involved recreation of the original design details and documentation of traditional weaving techniques and savoir-faire,” he says.

Not surprisingly, he won the Best Design (Country) Winner at IFS, London Fashion Week, in 2017, focusing on hand-made, sustainable, slow fashion and zero waste pattern making. His resume is impressive: Eleven Paris, he designed and developed a new line of leather shoes/bags.

Kaleekal knew at 21, he had to leave for Paris where he studied fashion design for three years. “Paris was professional, bootcamp, but fun. Watching Azzedine work in his studio was interesting, when I was interning there. No one was allowed to go in, it was his private space. Alaia told me how his grandma…I don’t remember whether it was paternal or maternal, was from Gujarat. I was struck by how precise he was in his cutting, thinking, and processes. Alaia didn’t like white models wearing white ensembles, he said the hue looks great on people with colour,” he says.

Alan grew up in Thiruvananthapuram and maybe it was his training with Rick Owens which shaped the way he is today. He came back in 2015, launched his label using premium fabrics, robust experience, and absorbed how the French work meticulously on details.

“I think I knew I had to develop my own aesthetics, and sensibility. I am not commercial, I don’t design ethnic things, I work on development of fabrics – Muga, Eri mulberry, cottons and wool in Ladakh,” he says. He also works with weavers from Kunjipalli Kerala, creating a custom designed satin fabric that is traditionally used in bedding.

His cerebral outlook is engaging, as he is now working on an ambitious project where he grew up – art gallery, library and lab. His untraditional ways also won him the British Council, British Fashion Council (BFC) and Mercedes-Benz ‘International Fashion Showcase Country Award in 2017.

His shapes are boxy, “which give you the liberty to move around, not body conscious, no hectic tailored pieces” he says, as he admits, he may have started almost ten years ago, in between he decided to take a break.

He was tired of seeing the same repetitive lehengas and wanted to be disruptive, thus unpredictable shapes, asymmetry became his lexicon. Some of his unexpected surprises are unstitched sides giving the wearer the liberty to close or not!

Maybe, it was his eclectic training at Gaultier which really turned things around. In 2012 he worked on India-based embroideries, fabrics, and prints. “It is tough to work in India, as I did things that are out-of-the-norm. The Press asked me how I will dress most of the Indian population which may not understand my ideology. I don’t think I have a perfect woman who embodies the spirit of my clothes, as design to me is deeply personal,” he says.

This is true as most Indians can’t get over embroideries, and if something doesn’t have shine or dripping with threadwork they ask, ‘Why is it so expensive, reduce the price?’

“I use no embroidery or embellishment…maybe sometimes lattice and kantha, but that’s not my main story, my focus is on pattern cutting. We also don’t do inspirations: pick a garden and tell a story,” he admits.

This year, for LFW the intellectual process begins with looking at things from a child’s perspective. “There is naivety, awkwardness and no garment is perfect. We tried to tell the wearer you can style things as you wish,” he concludes. – Asmita is the Lifestyle Editor of NRI Focus. She is an award winning journalist who has been writing on fashion for the last 32 years

Leave a Reply