One cannot really say whether it is his quest for perfection, which makes him the most coveted filmmaker to work with, or his painstaking research that even a sequin is not forgotten. What makes Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s cinematic excellence shine through is his eye for costumes that brings back a bygone era. Take for instance Bajirao Mastani in which Bhansali recreated the story of the Maratha Peshwa, Bajirao I (1700–1740), and his second wife, Mastani. The announcement of the film was made in 2003, but it saw the light of day only in 2015, owing to repeated cast changes. Bhansali meticulously worked out the finest details of the costumes and storyline because of which their thoughts aligned perfectly, says Delhi-based designer Anju Modi, who admits that working on costumes was a “stressful experience” as the Black creator expected only the best. Long hours of work and consistent brainstorming were the norm.

Anju, who has worked with Bhansali on many projects, narrates an interesting story. “Bhansali is a maverick with an intuitive mind. He doesn’t miss a single detail that the joke on the set was he could even see from his back,” she says.

“I remember the shooting of the song ‘Albela sajan aayo’ in which Priyanka Chopra would welcome Bajirao. Bhansali was throwing gulal in the air, in the spirit of celebration. It fell on Chopra’s sari. He asked me to make two more of those woven saris, for retakes. Each sari was nine yards long. I made two more and both of those also got stained. ‘I need four more saris in two days,’ Bhansali told me. I was paralyzed with fear; how could I create these saris, which take months to weave?” recalls Anju.Thankfully, after sleepless nights and hectic calls to the weaver, who said he had six woven saris, Anju could stitch them up together and create the nine yards Bhansali wanted. “I learnt a lesson that for any song, Bhansali’s shooting schedule would last over 15 days and so I must have at least five sets of costumes ready as a backup, and not wait for him to ask, just in case,” confesses Anju.

Anju recalls another incident when they were shooting the song ‘Mohe rang do laal’. She had created extra costumes, but what mattered were the emotions brought out by the fabrics. “The costume designs of a particular period in history were based purely on research – the ideas we got were largely from Indian miniature paintings that depicted an era. I learnt from an Italian designer on how to think ahead. I applied the technique for Bajirao Mastani. It felt like I was in a time machine, going on the reverse,” she laughs.

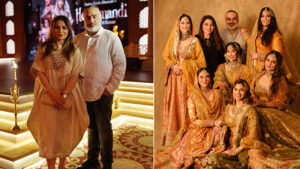

Delhi-based designers Rimple and Harpreet, who have also worked with Bhansali on the costumes for Heeramandi – recently aired on Netflix – pays tribute to the Lahore of the 1920s-1940s. The duo made almost 200 costumes, which must have cost a whopping several crores, each piece intricately crafted after ample research.“Bhansali has a certain world envisioned and the smallest details of every frame outlined in his mind. Some outfits are made in line with a lot of his inputs; that is where the cost shoots up and we want to do justice to his dream,” says Harpreet, who grew up in Ludhiana and is known for his soft approach and brilliant designs.

The husband and wife duo has travelled widely across India to procure fabrics for the costumes planned by Bhansali. “His shooting schedule sometimes has a rigorous demand on us to provide costumes in a very short span of time, so our production units go into overdrive,” says Rimple.

Does Bhansali give designers a free hand? “Right from our very first interaction with Bhansali during Padmaavat’s look test, he allowed us to not only use his research and inputs but also bring our own brand of design ethos to the table,” says Rimple.

Bhansali, discovered Rimple and Harpreet, at one of their couture shows in 2016, leading to the unforgettable collaboration on Padmaavat. Bhansali prioritizes functionality and wearability; costumes are therefore weighty, laden with layers of fabric, reflecting the wearer’s social status. Harpreet fits in with the filmmaker’s love for the embroidered past that reflects in his collection of vintage memorabilia. He has embroidered Suzani textiles from Uzbekistan, antique Parisian Jamawar shawls, and Palampore Kalamkari panels (that he has translated as prints for his couture collections), curios from Turkish flea-markets, and artworks by Spanish artists. “One of the most recent purchases is for our new Mumbai store, which we opened this month. I managed to get my hands on a four-poster Chinese opium bed, which is nearly 150 years old. It is very intricately carved with oriental symbology including dragons and other flora and fauna,” says Harpreet.

Rimple and Harpreet’s work requirements for both Heeramandi and Padmaavat were vastly different. “We used various elements when it came to motifs and embroideries related to specific provinces as envisioned by Bhansali,” says Harpreet. “Archival textiles, costumes, books and paintings, from museums such as the Calico Museum in Ahmedabad, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, as well as the self-portraits of Amrita Shergil gave us authenticity,” he says.

Heeramandi has a Punjab connection, so stories, anecdotes and experiences shared to Harpreet by his grandmothers and aunts helped enormously to picture a different time in history. Interestingly, in the TV series, you would see a lot of ghararas and sharara-ghararas that are very traditional in their construction – worn differently then, than how it is today. So now, the Indian runway can flaunt the revival of a silhouette that is suited for all body types, and can be worn across all age spectrums. – Asmita Aggarwal is Fashion & Lifestyle Editor of Nrifocus.com

Leave a Reply